I have the feeling that I’m very quickly going to slide into the next phase of this cancer journey…the phase where I start feeling better, start leaving the house more, start interacting with the outside world, and slow down on the updates. I’m already missing you and these blog posts.

What will this blog turn into then?

As you all know I love writing; maybe I’ll continue to devote time to words, maybe I’ll lose interest in the middle-of-the-night journaling thing (especially as I start sleeping more), or maybe I’ll dive into trying to put all of this into a book project (oooo, I said it out loud!).

No real secret here, but I’ve wanted to write a book since I started reading books…writing and reading have always been two of the most important things in my life, and I revere authors. I do! I’m so lucky to have many friends who have written books, and that makes the prospect achievable and a bit less daunting.

Here are some books that friends of mine have written:

- Married to the Trail – Mary Moynihan

- Adventure Ready – A Hiker’s Guide to Planning, Training, and Resliency – Katie Gerber and Heather Anderson

- Long Trails – Mastering the Art of the Thru-Hike – Elizabeth Thomas

- Hikertrash – Life on the Pacific Crest Trail – Erin Miller

- Thirst: 2600 Miles to Home – Heather Anderson

- Mud, Rocks, Blazes: Letting Go on the Appalachian Trail – Heather Anderson

- As the Trail Turns: Rag Short Stories Vol. 1: You Won’t Know Until You Get There – Amanda Timeoni

- As the Trail Turns Vol. 2: Hiker Trash Poems & Rag Stories – Amanda Timeoni (reading now!)

- Thru-Hiking Will Break Your Heart: An Adventure on the Pacific Crest Trail – Carrot Quinn

- The Sunset Route: Freight Trains, Forgiveness, and Freedom on the Rails in the American West – Carrot Quinn

- Bets – Carrot Quinn (reading now!)

- Best Day Hikes on the Arizona National Scenic Trail – Sirena Rana

- Urban Trails Tucson: Pima County * Saguaro National Park * Arizona National Scenic Trail – Sirena Rana

- Old Lady on the Trail: Triple Crown at 76 – Mary E. Davison

- Aren’t You Afraid?: American Discovery Trail from the Atlantic Ocean to Nebraska – Mary E. Davison

- I Hike – Lawton Grinter

- Halcyon Journey: In Search of the Belted Kingfisher – Marina Richie

- Becoming Odyssa: Adventures on the Appalachian Trail – Jennifer Pharr Davis

- Called Again: A Story of Love and Triumph – Jennifer Pharr Davis

- The Pursuit of Endurance: Harnessing the Record-Breaking Power of Strength and Resilience – Jennifer Pharr Davis

- Hiking the Oregon Coast Trail: 400 Miles from the Columbia River to California – Bonnie Henderson

- The Dehydrator Cookbook for Outdoor Adventurers: Healthy, Delicious Recipes for Backpacking and Beyond – Julie Mosier

- Ditch Walkers and Water Wars: the life and times of the Eldorado Ditch in the gold fields of Eastern Oregon – Mike Higgins & Les Tipton

- Hike366 – Jess Beauchemin

- How to Keep Playing for the Rest of Your Life – Jess Beauchemin

- Take Less. Do More.: Surprising Life Lessons in Generosity, Gratitude, and Curiosity from an Ultralight Backpacker – Glen Van Peski

Wow, I know some talented people! Making this list is also reassuring; I have a lot of resources and knowledge to turn to should I need it. These peeps have gone through traditional publishing houses and self-published. It runs the gamut. I’m not sure which way I would go…but I’m open to your suggestions and stories if you have them. Please check out the list above; I hope some of you find a new book or two to read. And here’s a plug for independent booksellers: buy from Bookshop.org if you buy online, or your local indy bookseller in person.

I think a book project will be worth it even if I write something that three people read (I’m looking at you Mom and Dad!), so maybe I’ll start putting something together that could be considered a book. (BTW, what are some good books about the writing process that you know of? I like John McPhee’s Draft #4: On the Writing Process, and Stephen King’s On Writing.)

If I’m diving into writing and reading in this post, I may as well talk about the time I read more books than ever…that’s the two years I spent sweating in my village of Zogore, Burkina Faso where my coping mechanism was reading. I read well over 200 books during that time and spent many, many hours hiding from the sun (and myself) by reading in my mud hut.

How did I even end up going into the Peace Corps in the first place? I can solidly place that portion of my life into the “I want to make a difference in the world” phase. (Hmmm, have I ever left that phase? Debatable.)

I can tell you what prompted me to turn in my application…

During my junior year of college, it was time to get an internship and put into practice all of the classwork I had been immersed in, which included a smattering of graphic design, communications, and writing courses. I wanted something creative, so I found one of the most creative positions I could in one of the least-creative industries: tractors. Peoria, Illinois was home to the Caterpillar tractors world headquarters at the time, and I found an illustrious position writing for the parts and service support newsletter.

I don’t want to knock Caterpillar. Many of my friends have worked or currently work for Caterpillar (including my brother Jeff), and there are many, many ties between the company and Bradley University. It was a natural fit to find an internship there (and I remember it paid really well!), but as I reported to my cubical in Morton, Illinois, in a sea of cubicles the same size, I quickly became disillusioned. I had a creative gig, oh yes! And the team of people I worked for were some fun creatives as well, but the output left something to be desired. I interviewed people, took photos, wrote articles and I had the great privilege of updating and designing the CCTVs around the Morton facility with the current day’s lunch menu. I alone could choose font colors and fun backgrounds. Fun!

Many of my classmates were gearing up for jobs in advertising agencies, PR firms, or ones like the Caterpillar gig, and I couldn’t be more turned off (sorry, not sorry). At Caterpillar, I worked in a cubical the same size as a guy who had been there 40 years, and I just couldn’t see myself there, so when the Peace Corps popped into my awareness, I jumped at it.

The application process was long. There were essays to write and letters of recommendation to get. There were medical tests to schedule and interviews to sit for. Honestly, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I wanted to have a grand adventure, and I had no real idea what being a Peace Corps volunteer would mean other than it was the exact opposite of the Caterpillar internship. Joining the Peace Corps would be a giant leap into the unknown, and if there is something I gleaned from reading thousands of books over my lifetime, it was that I had an eagerness for the unknown.

It was during spring break of senior year that I got the news of my Peace Corps assignment; I was going to the francophone country of Burkina Faso. I eagerly grabbed the first world atlas I could find, and there was no Burkina Faso. Hmmm. I had no idea what continent it was on…and couldn’t find it on a globe either. Where was I going???

It turns out Burkina Faso used to be Upper Volta until its name change in the 1980s, and the references I was using pre-dated the name change. (This was before the internet was everywhere…we had to wonder a lot before we had computers in our pockets!)

Ok, for the sake of time and effort (and a bit of laziness on my part at 2:02am) here is a chat GPT overview on the history on Upper Volta/Burkina Faso:

“Upper Volta, a landlocked country in West Africa, underwent a significant transformation to become Burkina Faso in 1984. This change was spearheaded by Captain Thomas Sankara, a charismatic and revolutionary leader who came to power in 1983 through a coup. Sankara sought to break the country’s ties to its colonial past and foster a sense of national identity and pride. The name “Burkina Faso,” meaning “Land of Incorruptible People” in the Mossi and Dioula languages, symbolized this vision of integrity and unity. Sankara implemented sweeping reforms, including land redistribution, promotion of women’s rights, and campaigns to eradicate corruption and improve health and education. Though his presidency was short-lived, Sankara’s renaming of the country remains a lasting legacy of his effort to redefine its future.”

Upper Volta had been colonized by the French, and Sankara successfully kicked out all the colonizers until his best friend, Blaise Compaoré, killed him and rekindled the foreign influences once again. “The coup was fueled by internal dissent and external pressures from powerful nations and regional actors who were uneasy with Sankara’s radical reforms and pan-Africanist stance. Compaoré’s takeover marked a sharp departure from Sankara’s revolutionary ideals. He justified the coup by accusing Sankara of endangering Burkina Faso’s international relationships. Under Compaoré, the country reverted to policies more favorable to Western interests, prioritizing economic liberalization over the socialist-inspired policies Sankara had championed. Compaoré ruled Burkina Faso for 27 years, during which his administration faced accusations of corruption, repression, and growing inequality, leaving Sankara’s vision of a self-reliant and equitable society unrealized.”

Peace Corps and all the other international development NGOs that typically blanket African nations didn’t start coming back until the 90’s. Our group of 1999 volunteers was only year 4 into the return to the country, and it was an interesting time to be in Africa. Overall, the Burkinabe welcomed us, they weren’t as jaded and corrupted by foreign influence as some of the neighboring countries, and the people still carried the pride of Sankara with them. They were an independent nation for a minute, they were going to be the future of Africa, they were a sign that things could be different.

But it was poor and struggling too.

“In 1999, Burkina Faso was ranked as the third poorest country in the world, with the majority of its population living on less than a dollar a day. The country’s economy was heavily reliant on subsistence agriculture, which employed around 80% of its workforce but remained vulnerable to erratic rainfall and desertification. Cotton was the primary cash crop, but fluctuating global market prices and a lack of industrialization limited its profitability. Burkina Faso’s economy also faced significant challenges, including a lack of natural resources, underdeveloped infrastructure, and limited access to education and healthcare. Despite its poverty, the country received international aid, and efforts were underway to implement structural adjustment programs encouraged by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). However, these reforms often placed a heavy burden on the rural poor, as subsidies were reduced and public services were privatized, exacerbating inequality and slowing progress toward sustainable development.” (thanks again Chat GPT)

So, 1999. I was going to Burkina Faso less than a month after graduating from Bradley; getting on the plane was one of the hardest things I had ever done to that point in my short and sheltered life. As I wrote about the other day, we had a few days in Washington, DC to get oriented before we left the country, and once we got there I just remember the heat. The plane door opening felt exactly like opening the oven door after baking a cake. The rush of hot air was overwhelming, and immediately after disembarking I remember one of our group immediately turned around and decided to go home. That rush of hot air was all it took for the reality of what we had signed up for to rush over her. I think we only lost one volunteer that day, but more dropped off as the three months of training went on. And plenty more left during the next two years. I think we showed up as a group of 45 in June of 1999, and left as a group of 25-30 in the summer of 2001.

I was surprised to find that I was one of the younger in our group. Many of my fellow volunteers had been working for a while, or were mid-career. Some were on their second Peace Corps tour, and several were quite a bit older. I was very naive about it all; I had envisioned that all of us were there to make a difference and to help make the world a better place. In reality, many of the other volunteers were there for their own personal reasons, and some even joined for a resume builder. These people were the most shocking to me. As soon as these folks got into med school or law school they were gone. I couldn’t wrap my head around it.

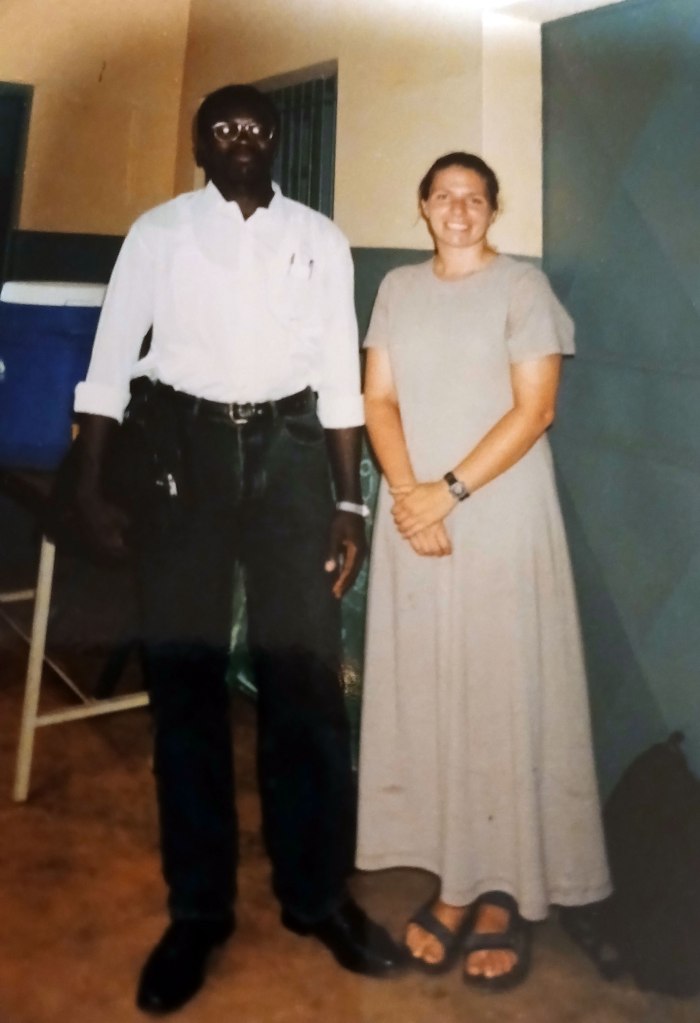

All in all, we bonded hard, that class of 1999. We came from all walks of life and from all over the country, and I still keep in touch with quite a few folks (hello all of you reading this!!)

So what was my job?? This is a great question. What is the job of the Peace Corps volunteer? It turns out they take the pressure off and consider ⅔ of being a volunteer as a cultural exchange. That means ⅓ of your job is being an American in the country. ⅓ is talking about your experience when you return (I’m working right now!) and ⅓ is the actual job you have been assigned to do in country. I was slated to be a health education volunteer, while many others were teachers. I wasn’t just a health education volunteer either…there were a small sub-section of us that were selected to help eradicate Guinea Worm. I’m not sure why I was selected for this special task, and I was literally freaked out by the prospect.

My AI friend tells me: “Guinea worm disease, a parasitic infection caused by consuming contaminated water, plagued many rural African communities in the late 20th century, trapping millions in cycles of pain and poverty. By the 1980s, the disease was particularly prevalent in countries with limited access to clean drinking water, including Ghana, Sudan, and Nigeria. Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and the Carter Center took on the eradication of Guinea worm as a major humanitarian mission starting in 1986. Through their efforts, the Carter Center collaborated with local governments, health workers, and international organizations to implement education campaigns, distribute water filters, and improve access to clean water sources. By the end of the 1990s, the eradication program had achieved remarkable progress, reducing the number of Guinea worm cases from an estimated 3.5 million in 1986 to fewer than 100,000 by 2000. This initiative highlighted the power of targeted health interventions and grassroots partnerships to combat neglected tropical diseases.”

The Carter administration had invested A LOT into the eradication efforts, and our Peace Corps group was essential to that goal. I was assigned to the small village of Zogore in the northern part of the country (not too far from Mali), and had 15 satellite villages under my purview. All of us volunteers were given shiny new green trek bicycles to get around our villages (riding mopeds was a no-no!), and my job was to help out the small health clinic in Zogore, and make progress in guinea worm eradication. I was also taught to do a health needs assessment and generally be of service to the community.

When I arrived in country, there were about 30 cases of guinea worm in the 15 villages I was in charge of, but the villagers really didn’t see the worm as a problem. You see, guinea worm usually proliferates during a rainy season. In the rainy season, there are more water sources that can be infected, and because the villagers were primarily subsistence farmers, they would drink out of these puddles, some becoming infected. Over the next 9-12 months the worm would grow in the infected farmer and burrow through muscle and tendons, growing about three feet long (ew!). From there it would form a hot boil in the foot or ankle just about the time of the rainy season the next year. To relieve the heat and pressure the farmer would walk into the fresh puddle and the worm would sense this and burst out of the body, sending millions of eggs into the water source, again, creating a nasty infected worm puddle for the next farmer to drink from as he was watering his crops. Essentially, worms were the sign of a good crop year. Worms popping out of the foot meant there would be water for growing food, and food meant there would be eating.

So we had to work against the tide of villagers not really seeing the guinea worm as a problem.

How did we fight the worm? Sometimes we just passed out simple filters in wooden frames…even filtering the pond water through a t-shirt would be enough to remove the worm larva. Then we had educational materials like picture books that we would bring with us to the villages which showed the life cycle of the worm.

A side note here: communication was tough. Basically, I had to learn French to communicate with the village health staff, and then the health staff had to speak the local language to the villagers. I walked around with a French/English dictionary most of the time, and got really good at talking around something when I couldn’t find the right word. Most of the villagers didn’t speak French, it was the colonizer’s language after all, they only learned French if they went to school, and many of them didn’t. There were over 50 different local languages in the country, and my region spoke Moore. I did learn some Moore, but not a lot. Not enough to tell them about the life cycle of the guinea worm and why it was a good idea to put your foot in a bucket when you felt the worm blister coming on. If you put your foot in the bucket until the worm popped out, then you could throw the worm juice onto the ground and not infect the rainy season puddles again.

Interestingly enough, the worm burrowing through the body wasn’t the main health concern, it was the open wound and inevitable infection that would form after the worm popped out. Picture a strand of angel hair pasta coming out of your leg. That’s about how thin the worm was, and the three feet of it didn’t leave the body all in one go, no. It took a few weeks for it to fully exit the leg, so common practice was to wrap the worm around a stick and give the stick a turn or two a day until it had fully come out. Pulling or cutting the worm out wouldn’t do any good…it would then calcify in the body and cause other problems, so the stick method was the way to go. And because these folks were farming shoeless in the dirt, infection on the foot or ankle was all but guaranteed.

Fighting the guinea worm was a challenge. It was an elusive and slow-moving fight. Sometimes, people would show up from the ministry of health with some chemicals that we would pour into a known infected water source, and sometimes a foreign NGO would just show up in the village to build a pump that would bring up clean water, water that couldn’t be infected. But usually, we just had to talk about the life cycle with our picture books and make visits to check in on people.

Let me tell you, it was crazy how foreign development worked in Burkina. People from random countries would just show up and do things, or build things, or drop things off for the villagers. There was little to no communication ahead of time, and they were often surprised to find a white 20-something american living in the village. Sometimes I would benefit from the visits and get a fun treat or chocolate or something, but often I was a distraction and didn’t fit into their neat narritive of coming to the rescue.

But, back to my job. The guinea worm stuff didn’t take up a lot of my time. When I did my needs assessment and really spent some time talking with the villagers and observing what many of them came into the health center for during the week, I determined that the greatest health needs of my village were very simple. Many of them came down to keeping the health center clean and reporting the right information back to the Ministry of health.

Nursing was a civil service job in Burkina Faso, and students from all over the country would go to school then get assigned to a village for a year or two to be a nurse. Same with the teachers that were often found in village. The nurses and teachers were usually not from the area, and they were some of the only other people who could speak French, so they became our friends. But because the nurses weren’t from the village, they didn’t always care so much about the villagers and doing their jobs.

Overall, I wanted the health clinic to be much cleaner, it was often disgusting. There were bats that roosted in the ceiling and bat droppings would fall onto all the surfaces. The paperwork was usually not filed in an orderly manner, and I spent many hours trying to straighten up and clean things. This was all important because when a villager did come in for a health reason, I didn’t want them to go away with an infection because of a dirty examination room. This was the most pressing health concern.

But the villagers didn’t always come. Many days, I would show up at the health clinic, and there was no one there. I would bring my book, or break out cards to play with the dudes that always seemed to show up and hang out around town. There were no set hours to keep, and no one cared when I showed up or didn’t show up, but with my American, type A personality, I went to the health clinic every day, even if the nurse didn’t leave their house. I would sit under the tree and at least be there. Many, many hours were passed during the two years just sitting under trees. It became difficult at times to feel like I was doing anything of importance, so would console myself in the ⅔ ratio of my job. I was doing ⅔ of my job just by being there! It was ok! I wasn’t failing!

Actually, making a difference during the Peace Corps was kind of a joke. We volunteers often felt useless. The teachers, too. Sure, teaching was important, but was an American volunteer displacing a local Burkinabe teacher who could have the job? Probably.

So I read books. I read a lot of books. There wasn’t much else to do. I drank millet beer, played cards, goofed around with the teachers, road my bike, and read. That was about it.

I could dig up countless stories, we had adventures, sure we did! We took vacations to the Ivory Coast where we got caught up in the coup of Christmas 2000, we went to Ghana and Togo. I had to get a root canal and they flew me to Senegal to the dentist! We survived Y2K on a beach, and I lived through stepping on a dirty hypodermic needle in one of the largest hot spots of AIDS in West Africa. Oh, there were the sicknesses too. I got Giardia about 5 times, amoebas, and other such parasites too. But mostly it was me and the books. I became really good at being alone. Sure, I was lonely and thought the world was passing me by, and had to constantly remind myself that I was the one having the adventure. That reading my 134th book was the adventure.

Actually, reading a book led me to my next big thing, hiking. I picked up There are Mountains to Climb during one of the first months in my village and instantly knew that hiking the Appalachian Trail would be my next thing. I only had two years to wait and think about that one!

But much like hiking, the best part of the whole experience were the people. In fact there is supposed to be a Burkina Faso Peace Corps reunion this August in Portland! It’s not just for our class either; it’s for all volunteers that were in the country, so that should be a blast.